import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import holoviews as hv

import hvplot.pandas # noqa

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from bokeh.models import FixedTickerObserving Climate Change from Space

10.1 Overview

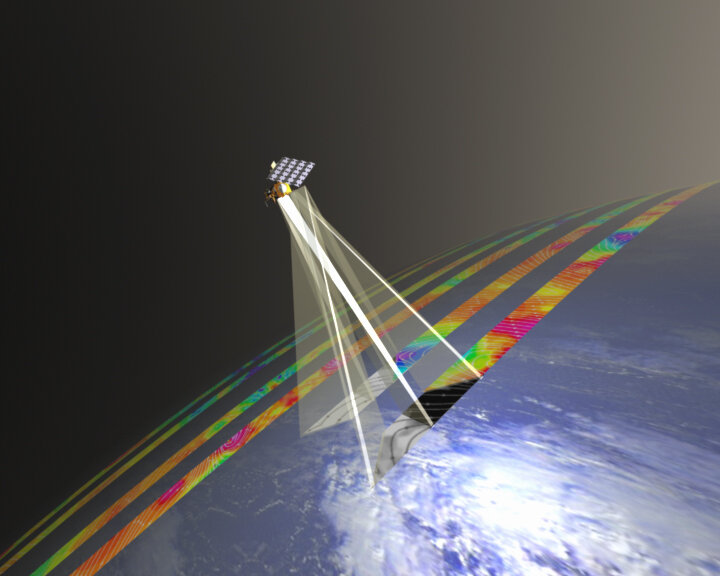

In this notebook we will examine the capabilities of H SAF Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) to monitor droughts in Mozambique. ASCAT instruments are situated onboard the Metop satellites (EUMETSAT1) that are in orbit around the Earth. Since 2007, these missions have yielded a continuous record of microwave backscattering and continue to produce data for the future. The longevity of the ASCAT microwave backscatter record is therefore well-suited to track climate change, such as, El Niño induced rainfall patterns over Mozambique. The surface soil moisture (SSM) retrieved from the product showcased here is available at a sampling distance of 6.25\(\,\)km, this means that one value of soil moisture is available for every 50\(\,\)km\(^2\) (5000\(\,\)ha).

More information about microwave backscattering and the fundamentals of surface soil moisture retrieval from microwave backscatter signatures can be found here:

10.2 Imports

10.3 Surface Soil Moisture of Mozambique (2007 - 2025)

Let us start by having a look at monthly aggregated SSM derived from ASCAT microwave backscattering over Mozambique. We can easily load the csv-file with pandas from the web, like so:

%run ./src/download_path.py

url = make_url("ascat-6_25_ssm_monthly.csv") # noqa

df = pd.read_csv(

url,

index_col="time",

parse_dates=True,

)

df.head()https://git.geo.tuwien.ac.at/api/v4/projects/1266/repository/files/ascat-6_25_ssm_monthly.csv/raw?ref=main&lfs=true| location_id | longitude | latitude | surface_soil_moisture | zscore | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | |||||

| 2007-01-31 | 10234428 | 32.357162 | -26.855516 | 21.400 | -0.598621 |

| 2007-01-31 | 10235038 | 32.621094 | -26.849566 | 22.970 | -0.788044 |

| 2007-01-31 | 10235648 | 32.885020 | -26.843615 | 21.355 | -0.857445 |

| 2007-01-31 | 10236025 | 32.457973 | -26.839937 | 20.990 | 0.160121 |

| 2007-01-31 | 10236635 | 32.721905 | -26.833986 | 29.640 | 0.171792 |

Now we plot the results with hvplot. This creates an interactive plot whereby we can map the SSM values on an Open Street Map (OSM) and scroll through all months from 2007 to the present. For convenience, we added the locations of the in-situ sensors placed for each target district in the DrySAT project. Note, that the SSM values are reported as the degree of saturation, so, in other words, how much of the surface soil pore space is filled with water. This, unlike commonly used volumetric units, which records how much of the soil’s volume is water.

%run ./src/ssm_cmap.py

locations = {

"Muanza": {"latitude": -18.9064758, "longitude": 34.7738921},

"Chokwé": {"latitude": -24.5894393, "longitude": 33.0262595},

"Mabote": {"latitude": -22.0530427, "longitude": 34.1227842},

"Mabalane": {"latitude": -23.4258788, "longitude": 32.5448211},

"Buzi": {"latitude": -19.9747305, "longitude": 34.1391065},

}

df_locs = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(locations, "index").reset_index()

points = df_locs.hvplot.points(

x="longitude", y="latitude", color="black", crs=ccrs.PlateCarree()

)

labels = df_locs.hvplot.labels(

x="longitude",

y="latitude",

text="index",

text_baseline="bottom",

text_color="black",

crs=ccrs.PlateCarree(),

)

df.hvplot.points(

x="longitude",

y="latitude",

c="surface_soil_moisture",

groupby="time",

x_sampling=0.08,

y_sampling=0.08,

rasterize=True,

crs=ccrs.PlateCarree(),

tiles=True,

cmap=SSM_CMAP, # noqa

clim=(0, 100),

frame_width=500,

clabel="Surface soil moisture (%)",

) * points * labels10.4 Surface Soil Moisture Timeseries

Now let us have a closer look at the five locations marked on the SSM map and plot the SSM values against time for these 5 locations—known as timeseries. To do this we have already filtered down the full dataset to only contain the five locations. This filtered dataset shows the full temporal resolution of the product. To visualize this, we highlight the density of data points falling in a certain sector of the plot with blue shading—bluer values mark a higher density of data points.

ts = pd.read_csv(

make_url("ascat-6_25_ssm_timeseries.csv"), # noqa

index_col="time",

parse_dates=True, # noqa

)

ts.hvplot.scatter(

x="time",

y="surface_soil_moisture",

groupby="name",

rasterize=True,

dynspread=True,

threshold=1,

frame_width=800,

padding=(0.01, 0.1),

clabel="Density of data",

)https://git.geo.tuwien.ac.at/api/v4/projects/1266/repository/files/ascat-6_25_ssm_timeseries.csv/raw?ref=main&lfs=trueThe cyclical seasonal pattern from dry to wet can be easily discerned from the timeseries. Note, however, again that we do not track precipitation, but the change from wet to dry soils. Moreover, we can see that the cyclical pattern breaks down on occasion as can be seen in the years 2015 and 2016. Especially Chokwé displays a complete lack of wet soils during the 2016 rainy season. We can remove some of the noise in the records by aggregating the values on a monthly basis, as can be seen in the following code chunk. Here, the pandas dataframe method groupby can group the timeseries for all successive months with the pandas function Grouper(freq="ME") and the location name.

ts_monthly = (

ts.groupby([pd.Grouper(freq="ME"), "name"])

.surface_soil_moisture.mean()

.reset_index(level="name")

)

ts_monthly.hvplot.line(

x="time",

y="surface_soil_moisture",

by="name",

frame_width=800,

padding=(0.01, 0.1),

)In these aggregated timeseries we can more easily see differences in the averages and amplitudes between the locations. The differences in the average value can be an artefact of looking at the degree of saturation, and thus properties of the soil, or can reflect climatic differences, where some locations are generally wetter or drier than other locations. However, the amplitude, or the magnitude of change in SSM over time, is of greater importance for drought detection, as we want to see if a change in SSM during a specific time is “normal”, or more “unusual”, when compared to other years.

10.5 Normalization and Anomaly Detection

To filter out these differences between locations, and to emphasize how “unusual” certain periods are, we calculate Z score statistics.

\[ z_i = \frac{x_i - \bar{x}}{s^x} \]

The Z score statistic is an approach to detect anomalies in timeseries, where one measures how far a datapoint (\(x_i\)) is removed from the mean (\(\bar{x}\)). This distance from the mean by itself is not all that useful, as it depends on the location’s average SSM. To circumvent, and to more easily compare timeseries of different locations, we divide the distance of the mean with a measure of variation of the timeseries, such as the standard deviation (\(s^x\)). In the following code chunk we implement the Z score as a python function for a pandas.Series.

def zscore(x):

return (x - x.mean()) / x.std()We exemplify this normalization step below. Here we can see two histograms for a simulated SSM dataset. The histogram on the left is still in the original “degree of saturation” units, whereas the graph on the right is transformed to Z scores. The value of the x axis of the right-hand figure can be translated as: “This point is so many standard deviations removed from the mean.”

np.random.seed(42) # make example reproducible

mu, sigma = 50, 10 # mean and standard deviation

random_ts = pd.Series(np.random.normal(mu, sigma, 100))

(random_ts.hvplot.hist() + zscore(random_ts).hvplot.hist()).cols(1).opts(

shared_axes=False

)10.6 Drought Anomaly Detection

For our real time series, we will take it one step further by calculating the average for all months of January and comparing this to the monthly totals. This approach is repeated for all months. This operation is similar to the previous groupby operation but now we transform the panda’s column and use the datetime accessor month to accumulate monthly averages.

ts_zscore = ts_monthly.groupby(

[ts_monthly.index.month, "name"]

).surface_soil_moisture.transform(zscore)

ts_zscore = ts_monthly.assign(zscore=ts_zscore)

ts_zscore.hvplot.line(

x="time",

y="zscore",

by="name",

frame_width=800,

padding=(0.01, 0.1),

)In the last plot we can now clearly discern the drought of 2015/2016 but also other droughts, such as during the years 2019/2020. The Z score also appears to indicate more than usual drought in 2024/2025.

10.7 Monitoring Drought in Time and Space

As a last step, we can now apply this approach to the whole of Mozambique. Here we have already calculated the Z scores and we just have to plot them.

colorbar_opts = {

"major_label_overrides": {

-4: "Extreme",

-3: "Severe",

-2: "Moderate",

-1: "Mild",

0: "Normal",

},

"ticker": FixedTicker(ticks=[-4, -3, -2, -1, 0]),

}

df[df.zscore <= 0].hvplot.points(

x="longitude",

y="latitude",

c="zscore",

groupby="time",

x_sampling=0.08,

y_sampling=0.08,

rasterize=True,

crs=ccrs.PlateCarree(),

tiles=True,

cmap="reds_r",

clim=(-4, 0),

frame_width=500,

clabel="Drought anomaly",

).opts(hv.opts.Image(colorbar_opts={**colorbar_opts})) * points * labelsThis temporospatial analysis (in time and space) confirms that 2015/2016 was particularly pronounced in the south of the country surrounding the region of Chokwé. But this intense drought was also prevalent in the northern districts neighbouring Malawi. This is something that would not be seen in a spot-wise analysis.

In the next notebooks, we will compare this microwave-based technique to other indicators of drought such as SPEI and vegetation-based indicators of drought (NDVI).