import folium

import hvplot

import hvplot.pandas

import pandas as pd

from envrs.download_path import make_urlComparing H SAF ASCAT Surface Soil Moisture with In-Situ Sensors

11.1 Overview

The aim of this notebook is to demonstrate and teach a workflow for validating ASCAT H SAF surface soil moisture (SSM) data, sampled at 6.25\(\,\)km distances, using in-situ sensors strategically placed in Mozambique. The evaluation in this context mainly assesses how well satellite-derived data aligns with the temporal patterns of in-situ soil water measurements. Remember, temporal dynamics are also crucial for anomaly detection in soil moisture records, which in turn affects our ability to monitor droughts (as discussed in the previous notebook). However, it is also a good practice to examine the absolute values of remotely sensed soil moisture. Such comprehensive validation processes are vital for forecasting, climate research, and decision-making, as they ensure the accuracy and reliability of weather data. By comparing different datasets, one can identify and address inconsistencies, thus enhancing the quality of meteorological records.

11.2 Imports

11.3 In-situ Soil Moisture Sensors

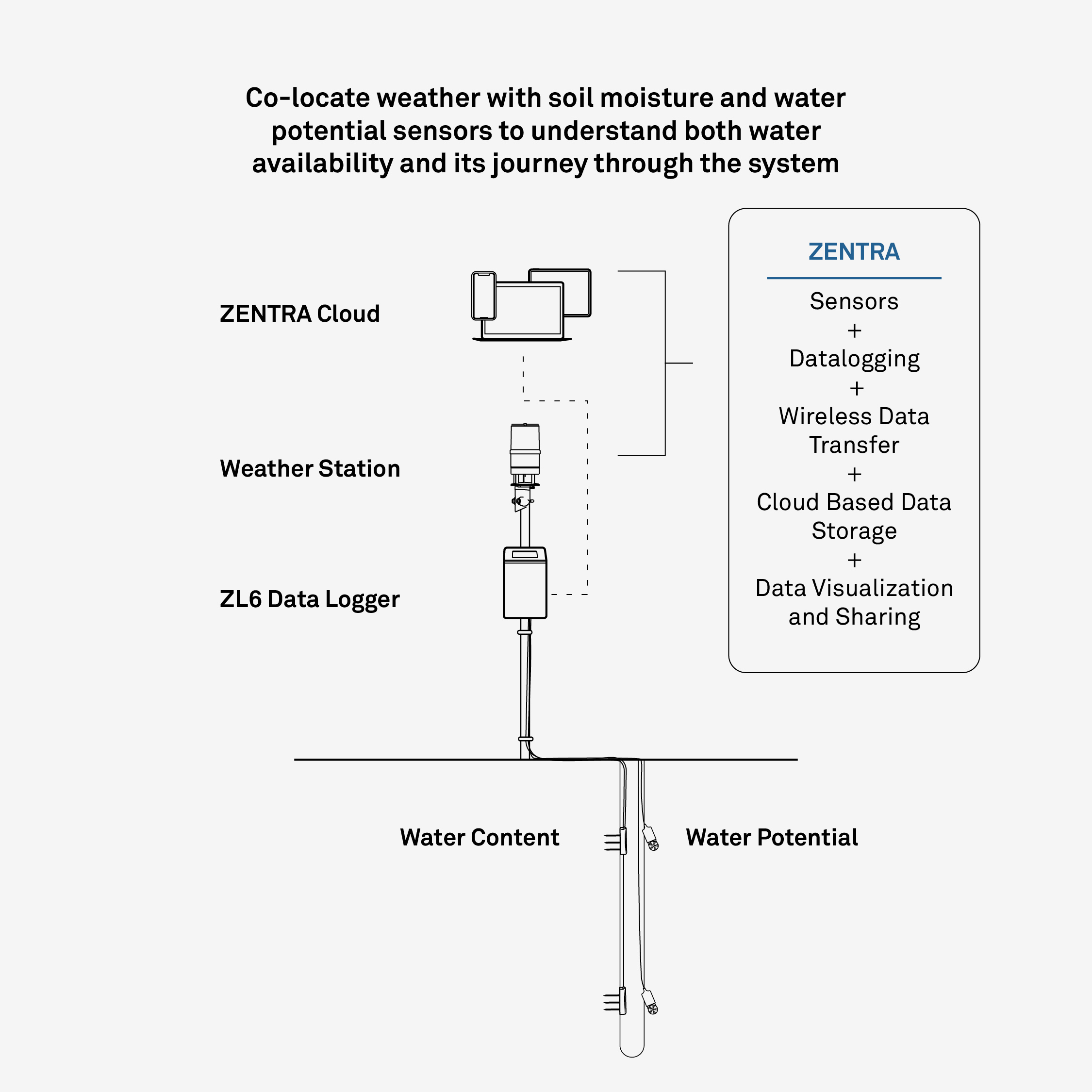

During the DrySat project we have placed 5 in-situ measuring stations (METER™, see image at the top) at strategic locations in Mozambique (Buzi, Chokwé, Mabalane, Mabote and Muanza). The locations are plotted on the following folium map for reference.

locations = {

"Muanza": {"latitude": -18.9064758, "longitude": 34.7738921},

"Chokwé": {"latitude": -24.5894393, "longitude": 33.0262595},

"Mabote": {"latitude": -22.0530427, "longitude": 34.1227842},

"Mabalane": {"latitude": -23.4258788, "longitude": 32.5448211},

"Buzi": {"latitude": -19.9747305, "longitude": 34.1391065},

}

map = folium.Map( # noqa: A001

max_bounds=True,

zoom_start=6,

location=[-20, 34],

scrollWheelZoom=False,

)

for i, j in locations.items():

folium.Marker(

location=[j["latitude"], j["longitude"]],

popup=i,

).add_to(map)

mapThese 5 stations each have 4 in-situ soil moisture sensors (Campbell Scientific™ HydroSense II with CS659) installed at depth intervals of 5, 10, 15, and 30\(\,\)cm. The deeper layers may not be directly pertinent to H SAF ASCAT SSM values, but they are important for another product derived from ASCAT data: the Soil Water Index, which assesses the moisture content of deeper layers. We will explore this further in a later notebook. The soil moisture content is measured every 15 minutes and directly stored in the cloud. Since their installation at the end of September 2023, these stations have continually gathered data. For this exercise, we have already cleaned and reformatted a portion of this dataset, which now includes only the measurements from the 5\(\,\)cm depth interval. Please consult us if you need access to the entire raw dataset.

It’s interesting to learn that the current in situ reference datasets are heavily focused on Europe and the USA (as seen on the ISMN MAP) due to data availability, which likely introduces bias into satellite products. Consequently, reference data from regions outside Europe and the USA are particularly valuable.

We load the data again as a pandas.DataFrame, like so:

RANGE = ("2023-09-30", "2025-05-06")

df_insitu = pd.read_csv(

make_url("insitu_ssm_timeseries.csv"),

index_col="time",

parse_dates=True,

)

mask = (df_insitu.index > RANGE[0]) & (df_insitu.index <= RANGE[1])

df_insitu = df_insitu[mask]

df_insitu.head()https://git.geo.tuwien.ac.at/api/v4/projects/1266/repository/files/insitu_ssm_timeseries.csv/raw?ref=main&lfs=true| name | type | surface_soil_moisture | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | ||||

| 2023-09-30 22:00:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:15:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106434 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:30:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:45:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106434 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 23:00:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

Next, we will load the H SAF SSM 6.25\(\,\)km data as we did in the previous notebook. This time, however, we will filter the data to include only dates for which both ASCAT and in situ measurements are available.

df_ascat = pd.read_csv(

make_url("ascat-6_25_ssm_timeseries.csv"),

index_col="time",

parse_dates=True,

)

mask = (df_ascat.index > RANGE[0]) & (df_ascat.index <= RANGE[1])

df_ascat = df_ascat[mask]

df_ascat.head()https://git.geo.tuwien.ac.at/api/v4/projects/1266/repository/files/ascat-6_25_ssm_timeseries.csv/raw?ref=main&lfs=true| name | type | surface_soil_moisture | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | ||||

| 2023-09-30 19:16:05.482000384 | Chokwé | ascat | 54.48 | % |

| 2023-09-30 20:08:26.582000128 | Chokwé | ascat | 49.17 | % |

| 2023-10-01 06:29:06.317000192 | Chokwé | ascat | 54.97 | % |

| 2023-10-01 07:21:28.896999936 | Chokwé | ascat | 46.66 | % |

| 2023-10-01 18:55:21.116000256 | Chokwé | ascat | 53.92 | % |

Note, that the units of the in situ measurements differ when compared to the H SAF ASCAT SSM data. The in-situ sensors record soil moisture in volumetric units as cubic meters of water per cubic meters of soil [m\(^3\) / m\(^3\)]. By contrast, the satellite derived estimates are presented as the degree of saturation in the pore spaces of the remotely sensed soil.

11.4 Degree of Saturation vs. Volumetric Soil Water Content

To enable an absolute comparison of both data sources, we will first convert the degree of saturation used in the H SAF ASCAT dataset to volumetric units. This will allow us to compare the satellite-derived estimates with the measurements from the in-situ sensors. To achieve this, we need to know the porosity of the soil at the sensor locations. If the porosity is unknown, we can estimate it using a fixed particle density and the location-specific bulk density, as shown in the following expression.

\[ \text{Porosity} = 1 - \frac{\rho_{\text{bulk}}}{\rho_{\text{particle}}} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Porosity} &\quad \text{: Total pore space in the soil (-)} \\ \rho_{\text{bulk}} &\quad \text{: Bulk density (in g/cm³)} \\ \rho_{\text{particle}} &\quad \text{: Particle density (in g/cm³)} \\ \end{aligned} \]

For your convenience, we have obtain the location-specific bulk density for our targeted areas in Mozambique from SoilGrids. The particle density is typically averaged at about 2.65 g/cm³1.

density_df = pd.DataFrame(

{

"name": ["Buzi", "Chokwé", "Mabalane", "Mabote", "Muanza"],

"bulk_density": [1.25, 1.4, 1.4, 1.35, 1.25],

}

).set_index("name")

density_df| bulk_density | |

|---|---|

| name | |

| Buzi | 1.25 |

| Chokwé | 1.40 |

| Mabalane | 1.40 |

| Mabote | 1.35 |

| Muanza | 1.25 |

We can now calculate the soil porosity from the bulk and particle density using the pandas transform method. After that, we will rename the column to “porosity”.

def calc_porosity(x: pd.Series) -> pd.Series:

"""Calculate Porosity.

Parameters

----------

x: Pandas.Series

Bulk Density

Returns

-------

Pandas.Series: Porosity

"""

return 1 - x / 2.65

porosity_df = density_df.transform(calc_porosity).rename(

columns={"bulk_density": "porosity"}

)

porosity_df| porosity | |

|---|---|

| name | |

| Buzi | 0.528302 |

| Chokwé | 0.471698 |

| Mabalane | 0.471698 |

| Mabote | 0.490566 |

| Muanza | 0.528302 |

Now we have the necessary information to convert the H SAF ASCAT SSM to volumetric units by using the following equation.

\[ \text{SSM}_{\text{abs}} = \text{Porosity} \cdot \frac{\text{SSM}_{\text{rel}}}{100} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{SSM}_{\text{abs}} &\quad \text{: Absolute soil moisture, how much of the total soil volume is water (in m³/m³)} \\ \text{SSM}_{\text{rel}} &\quad \text{: Relative soil moisture in the pore spaces (in \%)} \end{aligned} \]

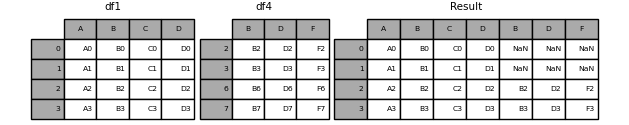

To apply this conversion to the HSAF dataset, we will first join the porosity values to the Soil Moisture (SSM) values based on the location names using a method called a “left join”. A left join in pandas merges two DataFrames while keeping all rows from the left DataFrame and adding matching rows from the right DataFrame. If there’s no match, it fills with NaN (see the figure for a schematic overview).

In this case, we’ll use the merge method, joining the left dataset on its ‘name’ column with the right dataset using its index labeled ‘name’.

df_ascat_porosity = df_ascat.merge(porosity_df, left_on="name", right_index=True)

df_ascat_porosity.head()| name | type | surface_soil_moisture | unit | porosity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | |||||

| 2023-09-30 19:16:05.482000384 | Chokwé | ascat | 54.48 | % | 0.471698 |

| 2023-09-30 20:08:26.582000128 | Chokwé | ascat | 49.17 | % | 0.471698 |

| 2023-10-01 06:29:06.317000192 | Chokwé | ascat | 54.97 | % | 0.471698 |

| 2023-10-01 07:21:28.896999936 | Chokwé | ascat | 46.66 | % | 0.471698 |

| 2023-10-01 18:55:21.116000256 | Chokwé | ascat | 53.92 | % | 0.471698 |

We can now use the pandas apply method to convert the units. This method takes the whole DataFrame as input allowing us to compute on two columns, while returning one column as output.

def deg2vol(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.Series:

"""Degree of Saturation to Volumetric Units.

Parameters

----------

df: Pandas.DataFrame

Degree of Saturation

Returns

-------

Pandas.Series: Volumetric Units

"""

return df["porosity"] * df["surface_soil_moisture"] / 100

df_ascat_vol = df_ascat.copy()

df_ascat_vol["unit"] = "m³/m³"

df_ascat_vol["surface_soil_moisture"] = df_ascat_porosity.apply(deg2vol, axis=1)

df_ascat_vol.head()| name | type | surface_soil_moisture | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | ||||

| 2023-09-30 19:16:05.482000384 | Chokwé | ascat | 0.256981 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 20:08:26.582000128 | Chokwé | ascat | 0.231934 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-10-01 06:29:06.317000192 | Chokwé | ascat | 0.259292 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-10-01 07:21:28.896999936 | Chokwé | ascat | 0.220094 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-10-01 18:55:21.116000256 | Chokwé | ascat | 0.254340 | m³/m³ |

11.5 Validation by Visual Inspection

The first step is to visually compare the time series. Visual inspection is essential for ensuring the validity and reliability of your results. It helps identify patterns and trends that might not be evident from data tables. Additionally, it is crucial for detecting outliers, which could indicate sensor malfunctions or data entry errors. In our case, we aim to see if both the in-situ and H SAF ASCAT SSM accurately reflect the characteristic seasonal rains of Mozambique.

To facilitate a clear overview, we will first concatenate the two datasets as follows:

df_combined = pd.concat([df_insitu, df_ascat_vol])

df_combined.head()| name | type | surface_soil_moisture | unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| time | ||||

| 2023-09-30 22:00:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:15:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106434 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:30:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 22:45:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106434 | m³/m³ |

| 2023-09-30 23:00:00 | Buzi | in-situ | 0.106400 | m³/m³ |

Next, we will use the hvplot extension for pandas to create interactive scatter plots for the time series.

df_combined.hvplot.scatter(

x="time",

y="surface_soil_moisture",

by="type",

groupby="name",

frame_width=800,

padding=(0.01, 0.1),

alpha=0.5,

)These plots already assure us that the trends in both data records align with the monotonic trends characteristic of soil wetting during Mozambique’s rainy season.

11.6 Quantitative Validation Metrics

We can now move to a more quantitative estimate. Correlation analysis is a valuable tool for validating meteorological records by comparing different datasets to ensure consistency and accuracy. It measures the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. In the context of meteorological records, it helps assess how well different datasets align with each other in terms of temporal dynamics, serving as a quality assurance measure.

Before applying correlation analysis, we need to reshape our DataFrame by pairing the data to the same timestamps for each of the five locations. For this, we will use the groupby method in combination with the resample method. The resample method will adjust the time index to a new frequency of 1 day, using the median value to down sample the frequencies from 15 minutes to daily for both ASCAT and in-situ sensor data.

df_insitu_daily = (

df_insitu.groupby("name")["surface_soil_moisture"]

.resample("D")

.median()

.to_frame("in-situ")

)

df_ascat_vol_daily = (

df_ascat_vol.groupby("name")["surface_soil_moisture"]

.resample("D")

.median()

.to_frame("ascat")

)

df_resampled = df_ascat_vol_daily.join(df_insitu_daily)

df_resampled = df_resampled.dropna()

df_resampled.head()| ascat | in-situ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| name | time | ||

| Buzi | 2023-10-01 | 0.068072 | 0.110634 |

| 2023-10-03 | 0.048498 | 0.113430 | |

| 2023-10-05 | 0.067623 | 0.113479 | |

| 2023-10-06 | 0.052117 | 0.113479 | |

| 2023-10-08 | 0.060834 | 0.112111 |

The data is now ready for correlation analysis. For time series analysis, if you’re looking at trends and expect a linear relationship, Pearson correlation is straightforward and precise method.

\[ r = \frac{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \bar{x}) (y_i - \bar{y}) }{ \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \bar{x})^2 } \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2 } } \]

where:

\[ \begin{aligned} n &\quad \text{: number of data points} \\ x_i \; \text{and} \; y_i &\quad \text{: individual sample points} \\ \bar{x} &\quad \text{: mean of the} \; x \; \text{values} \\ \bar{y} &\quad \text{: mean of the} \; y \; \text{values} \end{aligned} \]

The Pearson correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to 1:

- \(r = 1\) indicates a perfect positive linear relationship.

- \(r = -1\) indicates a perfect negative linear relationship.

- \(r = 0\) indicates no linear relationship.

We implement this with pandas, as follows:

df_resampled.groupby("name").corr(method="pearson")| ascat | in-situ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||

| Buzi | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.663829 |

| in-situ | 0.663829 | 1.000000 | |

| Chokwé | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.644887 |

| in-situ | 0.644887 | 1.000000 | |

| Mabalane | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.729945 |

| in-situ | 0.729945 | 1.000000 | |

| Mabote | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.584710 |

| in-situ | 0.584710 | 1.000000 | |

| Muanza | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.669616 |

| in-situ | 0.669616 | 1.000000 |

Use Spearman correlation when the relationship between your time series is not necessarily linear but generally moves in the same direction (monotonic).

\[\rho = 1 - \frac{6 \sum d_i^2}{n(n^2 - 1)} \]

where:

\[ \begin{aligned} n &\quad \text{: number of observations} \\ d_i &\quad \text{: difference between the ranks of corresponding values} \; x_i \; \text{and} \; y_i \end{aligned} \]

The interpretation of \(\rho\) is the same as for the Pearson’s correlation (\(r\)) coefficient. Spearman is great for data where the ranking of values is important and is less affected by outliers and non-normal distributions. This makes it a robust choice for various types of data. It’s also easy to interpret because it focuses on the overall trend.

df_resampled.groupby("name").corr(method="spearman")| ascat | in-situ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| name | |||

| Buzi | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.652317 |

| in-situ | 0.652317 | 1.000000 | |

| Chokwé | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.595828 |

| in-situ | 0.595828 | 1.000000 | |

| Mabalane | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.754692 |

| in-situ | 0.754692 | 1.000000 | |

| Mabote | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.720681 |

| in-situ | 0.720681 | 1.000000 | |

| Muanza | ascat | 1.000000 | 0.593781 |

| in-situ | 0.593781 | 1.000000 |

The correlation coefficients for both Pearson and Spearman methods range between 0.6 and 0.8 across different locations, indicating moderate to high positive correlations between the ASCAT HSAF 6.25\(\,\)km data and the in-situ soil moisture estimates.

So far, we have only evaluated relative temporal trends in the two data sources. However, it is clear from the visual comparison of HSAF ASCAT SSM and in situ soil moisture that there are also absolute differences. To quantify these differences, we will first calculate the bias between in situ and remotely sensed soil moisture. Using Pandas, this involves comparing the mean of the target values (remotely sensed SSM) to the mean of the reference values (in situ SSM). Bias is determined by the difference between these means.

\[ \text{Bias} = \bar{x}_i - \bar{y}_i \]

where:

\[ \begin{aligned} \bar{y}_i &\quad \text{: mean target value (remotely sensed SSM)} \\ \bar{x}_i &\quad \text{: mean reference value (in situ SSM)} \end{aligned} \]

Which we can easily implement, like so:

(

df_resampled.groupby("name")["in-situ"].mean()

- df_resampled.groupby("name")["ascat"].mean()

)name

Buzi 0.001074

Chokwé 0.012045

Mabalane -0.061894

Mabote -0.071499

Muanza -0.040774

dtype: float64Above, we observe the systematic error (in m\(^3\)/m\(^3\)) for each location. The H SAF ASCAT values are generally lower than the paired in situ observations, with the exception of Chokwé and Buzi. However, these differences are relatively small.

An interrelated yet distinct statistic is the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

\[ \text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - x_i)^2 } \]

where:

\[ \begin{aligned} n &\quad \text{: number of observations} \\ y_i &\quad \text{: target value (remotely sensed SSM)} \\ x_i &\quad \text{: reference value (in situ SSM)} \end{aligned} \]

Whereas bias contributes to the overall error measured by RMSE, RMSE captures both the bias and the variance components of the error. The relationship can be expressed through the bias-variance tradeoff:

- Bias: Reflects the absolute difference among in situ and remotely sensed soil moisture

- Variance: Reflects the relative differences among in situ and remotely sensed soil moisture

- Irreducible Error: The inherent noise or randomness in the data that cannot be explained

The total error, as captured by RMSE, can be broken down as:

\[ \text{Total Error (RMSE)} = \text{Bias}^2+\text{Variance}+\text{Irreducible Error} \]

This can be implemented, as follows:

def rmse(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.Series:

"""Root Mean Square Error.

Parameters

----------

df: Pandas.DataFrame

Target "ascat" and reference "in situ" columns

Returns

-------

Pandas.Series: Root Mean Square Error

"""

return ((df["ascat"] - df["in-situ"]) ** 2).mean() ** 0.5

df_resampled.groupby("name").apply(rmse)name

Buzi 0.066416

Chokwé 0.071972

Mabalane 0.074553

Mabote 0.082575

Muanza 0.060688

dtype: float64Here, we see that the RMSE ranges between 0.06 and 0.08 [m\(^3\) / m\(^3\)], which is small compared to the total range of H SAF ASCAT SSM. As a final step, we can visualize the relation of target (remotely sensed SSM) and reference values (in situ soil moisture) using hvplot.

hvplot.scatter_matrix(df_resampled.reset_index(level=0), c="name", alpha=0.3).opts(

plot_size=300

)Here, we observe that the relationship between in-situ and remotely sensed values is not entirely linear. Additionally, it indicates that soil moisture data is generally not normally distributed.

11.7 Scale of Measurement

We can only speculate about the reasons for the absolute and relative discrepancies, but it is important to note that the scale of in-situ measurements, which cover several centimeters around the device, compared to the averaged soil moisture value obtained by ASCAT, which encompasses about 50\(\,\)km\(^2\), might be a significant factor in explaining these differences. One can wonder what an averaged signal over such a broad area encompasses, as it can include a range of geomorphological, hydrological, and geological settings. Additionally, weather patterns can be confined to scales smaller than this area.

Rühlmann, M. Körschens, and J. Graefe, A new approach to calculate the particle density of soils considering properties of the soil organic matter and the mineral matrix, Geoderma, vol. 130, no. 3, pp. 272-283, Feb. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.01.024.↩︎